Whether it's the season's cool, crisp air or leaf-peeping adventures calling you outdoors during autumn, you can be sure of one thing when you step out into nature: Ragweed allergies will be waiting.

What is ragweed?

The ragweed plant, also known by the scientific name Ambrosia artemisiifolia, is a common culprit of late summer and fall allergies, causing sniffles and sneezes for 15 to 20% of Americans. And it's no wonder – not only is ragweed found in every U.S. state except for Alaska, it has a knack for survival. It thrives in poor soils. Its seeds remain viable for years. And it takes root in dirt practically everywhere, from roadsides to your rose garden.

Although ragweed is an annual, meaning it lives for only one growing season, a single plant can produce up to 1 billion pollen grains. What's more, those grains are so featherlight that they can travel for hundreds of miles on a breeze. According to the Asthma and Allergy Foundation of America, they've been detected as far as 400 miles out to sea and as high as two miles, the equivalent of eight Empire State Buildings, above ground.

How climate change affects ragweed pollen levels

As if ragweed isn't hardy enough, the warming climate is fortifying these nuisance plants in a number of ways.

For one, warmer air temperatures are making ragweed season last longer. Autumns across the contiguous U.S. have averaged 2.5 degrees Fahrenheit (1.4 degrees Celsius) warmer since 1970, which in turn has delayed first fall frosts by an average of 11 days. It takes temperatures of 25 to 28 F, or what's known as a moderate freeze, to kill ragweed. But as global warming keeps temperatures balmier later in the calendar year, the August-through-September ragweed season that traditionally occurred across much of the U.S. now lingers well into November in some states.

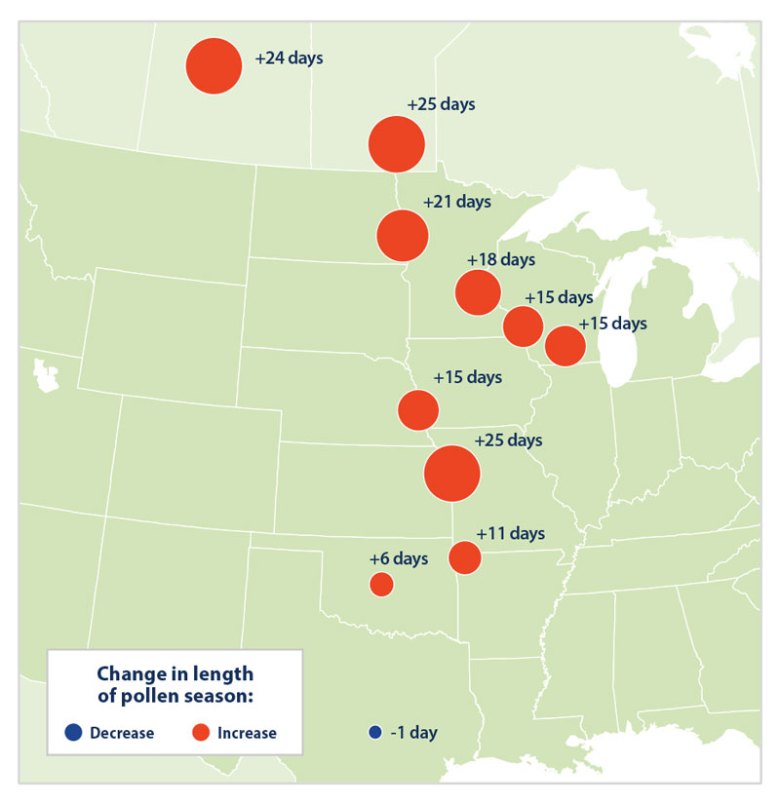

With temperatures rising faster at higher latitudes, the northern U.S. is experiencing the most extreme lengthening of ragweed season. For example, in Minneapolis, Minnesota, where average autumn temperatures have risen by nearly double the U.S. rate, the length of ragweed pollen season has expanded by over 2.5 weeks.

What's more, the longer air temperatures remain pleasantly mild, the later into the year people will flock outdoors to enjoy them, all the while increasing their exposure to airborne allergens.

North American map showing the change in ragweed pollen season length for 11 cities, including (from south to north) Austin, Texas; Oklahoma City, Oklahoma; Rogers, Arkansas; Papillion, Nebraska; Madison, Wisconsin; Lacrosse, Wisconsin; Minneapolis, Minnesota; Fargo, North Dakota; Winnipeg, Manitoba; and Saskatoon, Saskatchewan. Between 1995 and 2015, ragweed season lengthened up to 25 days in parts of the US and Canada. (Source: EPA)

In a warmer world, ragweed will likely expand its range northward, too. Although the nuisance weed is already present in northeastern states like New York and New Hampshire, its documented distribution is limited to their southern parts. But one 2018 study projects that under a worst-case, high-emissions global warming scenario in which neither carbon dioxide concentration levels nor average temperatures stabilize before 2100, ragweed is likely to expand across and north of Albany, New York; Montpelier, Vermont; Concord, New Hampshire; and Augusta, Maine, within the next 30 years.

In addition to rising temperatures, climate change's more frequent and intense droughts encourage the already lightweight ragweed pollen to spread more easily in the wind. Whereas moist air can clump pollen, weighing it down surfaceward and away from sinus passages, dry conditions keep it loose and airy.

Rising carbon dioxide concentrations supercharge ragweed

Climate change isn't just enabling ragweed to push farther north, it's also changing the species' biological life cycle. Higher carbon dioxide concentrations encourage ragweed plants to grow larger, flower more quickly, and produce heavier seeds, according to research published in the American Journal of Botany.

In another study, researchers observed carbon dioxide's ability to heighten ragweed's "allergenicity" – that is, its potential to trigger an allergic response in humans. They subjected ragweed plants to ambient and elevated (700 ppm) carbon dioxide levels. Then they extracted the pollen and administered it to test subjects. The researchers found that the pollen grown under elevated carbon dioxide conditions increased the amount of the plant's major allergen protein, Amb a 1, and also caused stronger allergic lung inflammation. This finding suggests that recent increases in carbon dioxide have already increased the severity of fall allergy seasons, and its projected rise will continue to do so in future years.

How to reduce ragweed allergy symptoms

This research paints a bleak future for allergy sufferers, but there's no need to panic-buy your favorite over-the-counter antihistamine just yet. Taking extra precautions when outdoors can also help.

First and foremost, if you have a ragweed sensitivity, try to limit any outdoor activity until after 3 p.m., because ragweed pollen counts peak in the mornings and at midday.

What if you must go out during the daytime, for example because you work outdoors? In that case, KN95 or N95 respirators (familiar sights during the COVID crisis) will largely filter out any ragweed pollen you'd otherwise inhale. Covering your hair with a baseball cap or bandana and checking your local pollen forecast before heading out the door are also good habits to adopt.

When returning home, be conscientious about tracking pollen indoors. Simple steps like removing your shoes outside, storing "contaminated" items in a mudroom, immediately changing into indoor-only clothes, and showering before bed, can help keep pollen at bay.

The good news is ragweed season usually ends by mid-to-late November. After that, you'll be able to breathe easier – that is, until indoor mold and dust make you sneeze. True to the old adage, there is no rest for the (allergen) weary.

This article was written by Tiffany Means and originally appeared on Yale Climate Connections.

Follow The Cool Down on Instagram and subscribe to our newsletter.